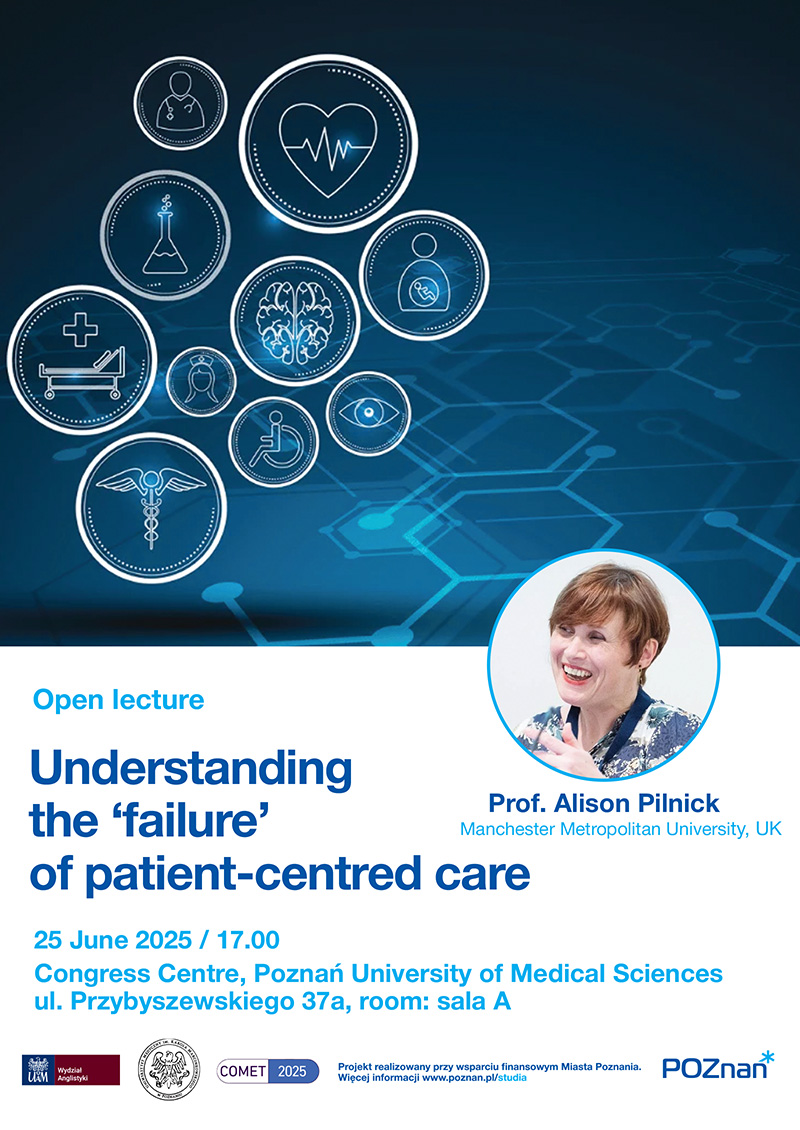

On behalf of the organizers of the 23rd International and Interdisciplinary Conference on Communication, Medicine and Ethics (COMET 2025), organized by the Faculty of English at Adam Mickiewicz University and the Poznań University of Medical Sciences, we cordially invite you to the open lecture by Prof. Alison Pilnick (Manchester Metropolitan University, UK) entitled Understanding the ‘failure’ of patient-centred care, which will take place on 25 June 2025 at 17:00 in Room A of the Poznań University of Medical Sciences Congress Centre (Centrum Kongresowo-Dydaktyczne Uniwersytetu Medycznego im. Karola Marcinkowskiego w Poznaniu), Przybyszewskiego 37a, Poznań.

Conference website [external link]

Abstract

Patient-centred care (PCC) is typically framed as a means to guard against the problem of medical paternalism, exemplified in historical attitudes of ‘doctor knows best’. In this sense PCC is often regarded as a moral imperative. However, systematic reviews of the adoption of PCC in healthcare settings do not find any consistent improvement in health behaviours or outcomes as a result. Rather than raising more fundamental questions about the approach, these findings are generally interpreted as pointing to the need for more or ‘better’ staff training. As a result, empirical research is often focused on the extent to which practice does or does not live up to checklists of PCC criteria, though these checklists are many and varied, and can produce conflicting results.

Patient autonomy is generally foregrounded in conceptualisations of PCC, to be actualised through the exercising of choice and control. But examining healthcare interaction in practice using conversation analysis shows that when professionals attempt to enact these underpinnings, it often results in the sidelining of medical expertise that patients want or need. Drawing on a large corpus of audio and video recorded healthcare interactions collected over 25 years from a wide range of practice settings, I will argue that in rightly problematising unbridled medical authority, PCC has inadvertently also problematised medical expertise. The end result is that patients can feel abandoned to make decisions they feel unqualified to make, or even that care standards may not be met. Understanding this helps to explain why PCC has not produced the hoped-for improvement in health outcomes. It also shows the importance of analyses of healthcare interaction for healthcare policy. The broad moral principles of a values-based approach may be attractive to policy makers but may also create intractable interactional dilemmas for practitioners who have to talk these policies into being.